Hoorah - I'm blogging again after a too-long absence - it feels good!

Yesterday, my friend Jenny and I visited the excellent

York Castle Museum to view the early 18th century Heslington Baby House. Our visit was a tale of two parts:

PART ONE

We were a bit disappointed to find that the Baby House is currently being displayed as part of a Georgian room setting and is situated at the far side of the room which can only be viewed from a barrier at the entrance.

|

The Heslington Baby House, 1700-1720*

(A.K.A The Yarbugh Baby House)

|

*Dates displayed on the information card for the baby house at the museum.

The distance from us, together with the necessarily low lighting in the museum, made satisfactory viewing of the rooms and contents impossible.

Additionally, three of the rooms couldn't be viewed at all because the opening fronts were closed.

One of the very helpful museum staff members told us that the museum does try to move exhibits about so that they are sometimes in room settings but at others they are behind glass and more easily viewed. However, being extremely heavy, the baby house isn't moved very often due to concerns about damaging it.

I think we must have looked very disappointed and a tiny bit desperate too because the member of staff also casually mentioned that the room in which the Baby House is situated is alarmed!

Now I don't particularly like blogging without photos, but we really couldn't see much and, not surprisingly, I didn't get any decent photos, so I'll keep this part brief, but I must mention something that made me chuckle when I was reading up on the house after our visit.

|

A photo of a photo of the unusual kitchen in

Constance Eileen King's book (mentioned below). |

The Heslington Baby House is the same house referred to as "The Yarburgh Baby House" in Vivien Greene's Family Dolls' Houses (1973) and in Constance Eileen King's The Collector's History of Dolls' Houses (1983).

In her book, Vivien Greene provides some information about about the Yarbugh family of Heslington Hall and a family marriage to the eminent architect Sir John Vanbrugh. Despite a lack of any concrete evidence, she concludes that it is:

"...likely that he [Vanbrugh] designed the Baby House for her many young sisters at an earlier date.."

Ten years later, in

her book, Constance Eileen King delivers a sharp reprimand to Vivien when she writes:

"Vanbrugh's style has been optimistically detected in the arched door, a favourite device, and used to perfect effect in the Orangery at Kensington Palace, and also in the shape of a shallow display-niche in the dining-room, but these designs were so basic to hundreds of country craftsmen, usually making only the most primitive furniture, that they can hardly be used as proof of the master's hand. One can only imagine the chagrin of an architect as fastidious as Vanbrugh at having such a clumsily structured edifice linked with his name."

and she later adds:

"The constant desire among doll's house enthusiasts to link the names of great architects to the models is almost always unfortunate. The houses are charming objects in their own right and hold just as much historical interest when they stand without improbable attributions such as Vanbrugh."

Ouch! I don't suppose that went down well. But I must say that I do agree with Ms. King.

PART TWO

This part of our visit was much more rewarding than the first!

A complete surprise to me was the existence of a second, later, but totally fabulous dolls' house on display at the museum - Dulce Domum (Sweet Home in Latin).

|

| Dulce Domum, c1885. |

This house was much easier to view as it was displayed behind glass, and it was just wonderful!

|

The name of the house and the initials of

Phyllis Dulce Warwick above the entrance. |

There was no information about the house on display, however, we were told by another helpful member of staff that it was given to Phyllis Dulce Warwick in 1885, though curiously, that date doesn't tie in with the 1891 Census in which Phyllis is listed as being three years old. She is also listed as being thirteen years old in the 1901 Census.

Anyway, unless I have the wrong Phyllis Dulce Warwick entirely, she was living at Chantry House, Newark when she was three but her family moved to Upton Hall, near Southwell, Newark soon after and that's where she spent the majority of her childhood. Her father was a brewer in the the family business.

I wonder how the house ended up in the York museum.

|

| The original fancy brass light-switches on the side of the house. |

We were also told that the house was unusual in that it was electrified when it was made and it therefore had electric lights well before many real houses had them.

Being behind glass made it a little difficult to photograph the house, but here are the best of my photos:

|

| Four storeys and eleven glorious rooms! |

|

| Bedroom - top floor left. |

|

| Bedroom - top floor right. |

|

| Landing - top floor centre. |

|

| Bedroom - second floor left. |

|

| Extra-wide Drawing Room - first floor left. |

|

| Drawing room - first floor right. |

|

| Dining Room - ground floor left. |

|

| Kitchen - ground floor right. |

|

| Hallway - ground floor centre. |

And finally, a few close-ups of some of the treasures:

|

| Colourful treen (?) in the dining room. |

|

| Beautifully shaped and decorated plant pot in a bay window. |

|

| A very sweet and tiny pug on a cushion. |

|

| A very grand-looking clock. |

|

| One of several fabulous treen sets. |

|

| Matching side tables in different rooms. |

|

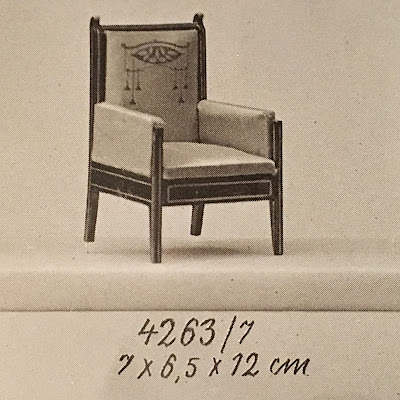

| An utterly gorgeous set of upholstered metal dining chairs and matching rocker in the large drawing room. |

I hope you enjoyed this tour and if you ever find yourself in York, I can strongly recommend a visit to the Castle Museum which has

many other interesting exhibits exhibits - Jenny and I ran out of time and plan to go back again soon.

Until next time,

Zoe